Interview & Text : Satoshi Taguchi

年齢のせいか目覚めるのが早くなった。日の出の頃には起きてしまう。好物はお茶。毎朝、日本茶や昆布茶を選んで淹れ、ひと息つく。餌を与える飼い猫(ゴン)は19歳。お互いに歳をとったと感じる。それから家のことを済ませたり朝の散歩をしたりして、撮影に出かけるのは午前10時。バックパックの中にはハッセルブラッドと80ミリの標準レンズ、そして数本のブローニーフィルムと露出計だけ。急行に乗って多摩川を越える。地下鉄を乗り継いで浅草へ。門前の商店が開きだす11時すぎに到着する。浅草寺に着くと、まず始めにいつも背景にしている朱塗りの壁へ。光の具合と状態を確認し、汚れていたらそれを落とす。そして境内でじっと待つ。やってくる人を見ながら、裸の目が撮りたいと感じる人をひたすら待つ。

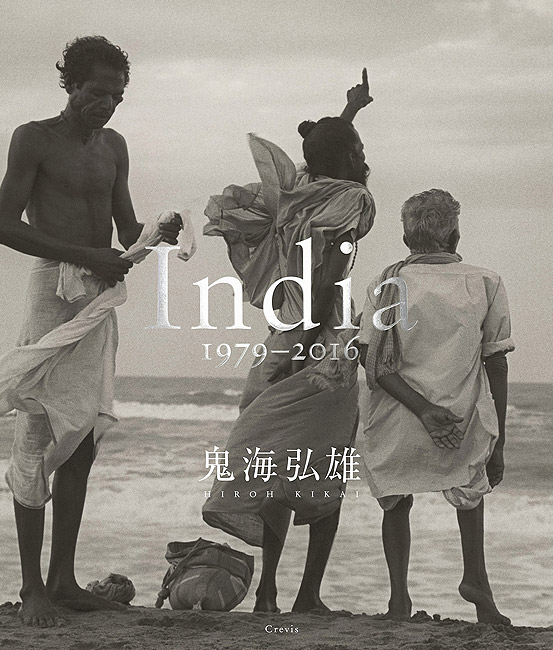

運がよければ日に3人も出会えることもあるけれど、だいたいは1人。もちろん3時間待って空振りの時もある。「この人こそ」という人に声を掛けて、体なく断られることもあるし、最近は無視されることも増えた。コミュニケーションの断絶を感じる。時には気分を変えるために出る時間を変えたりもする。夏の暑い盛りにはいくぶんの涼しさを求めて、始発でやってきたり、冬には冷えきった体をおでん屋で温めるために、午後に家を出たり。あるいはこのポートレイトの連作と並行して撮り続けてきた、「東京の街の肖像」や「インドやトルコでの流浪のスナップ」に月日を割くこともある。それでもやはり、写真家は多くの時間を待って過ごしている。浅草寺の片隅で、ただひたすら。鬼海弘雄の写真家としての40年は、そんなふうにして過ぎていった。そうやって生み出された写真には「何か」が写り込んでいる。心が揺さぶられる。積み重ねた膨大な時間が糧となり、そこに呼吸している。

何度も聞かれたであろうことを、再び聞かざるを得ないのが申し訳ない。けれど聞きたい。

ー どんな人を待っているのですか。

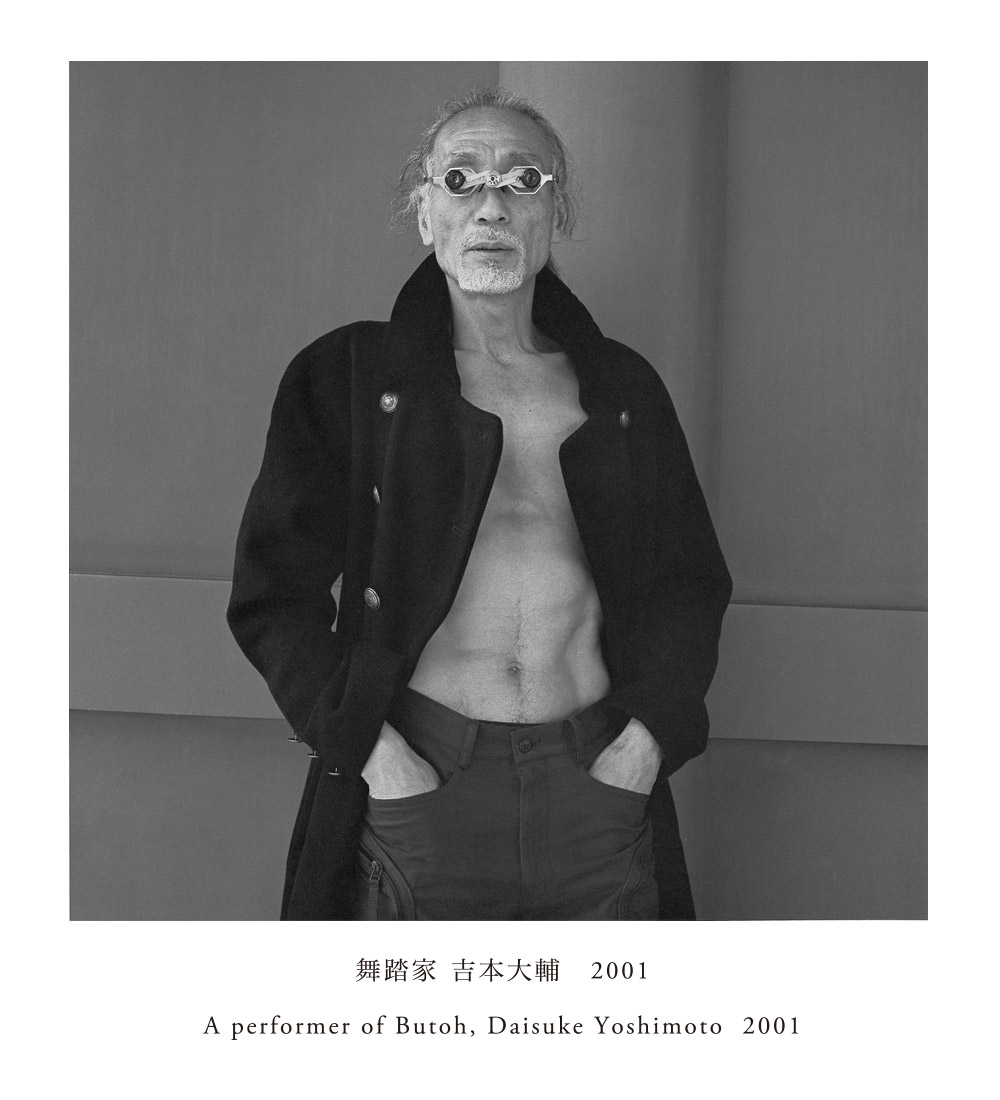

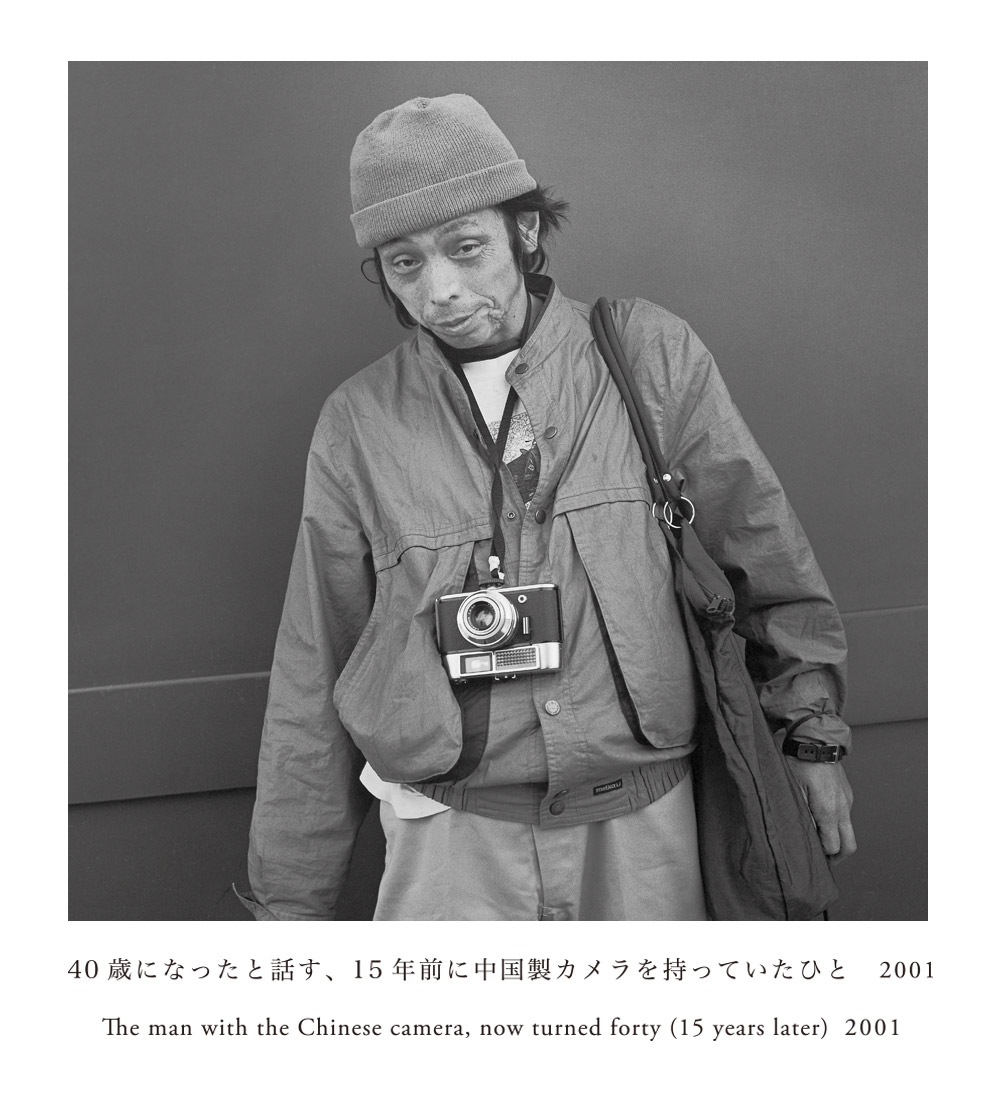

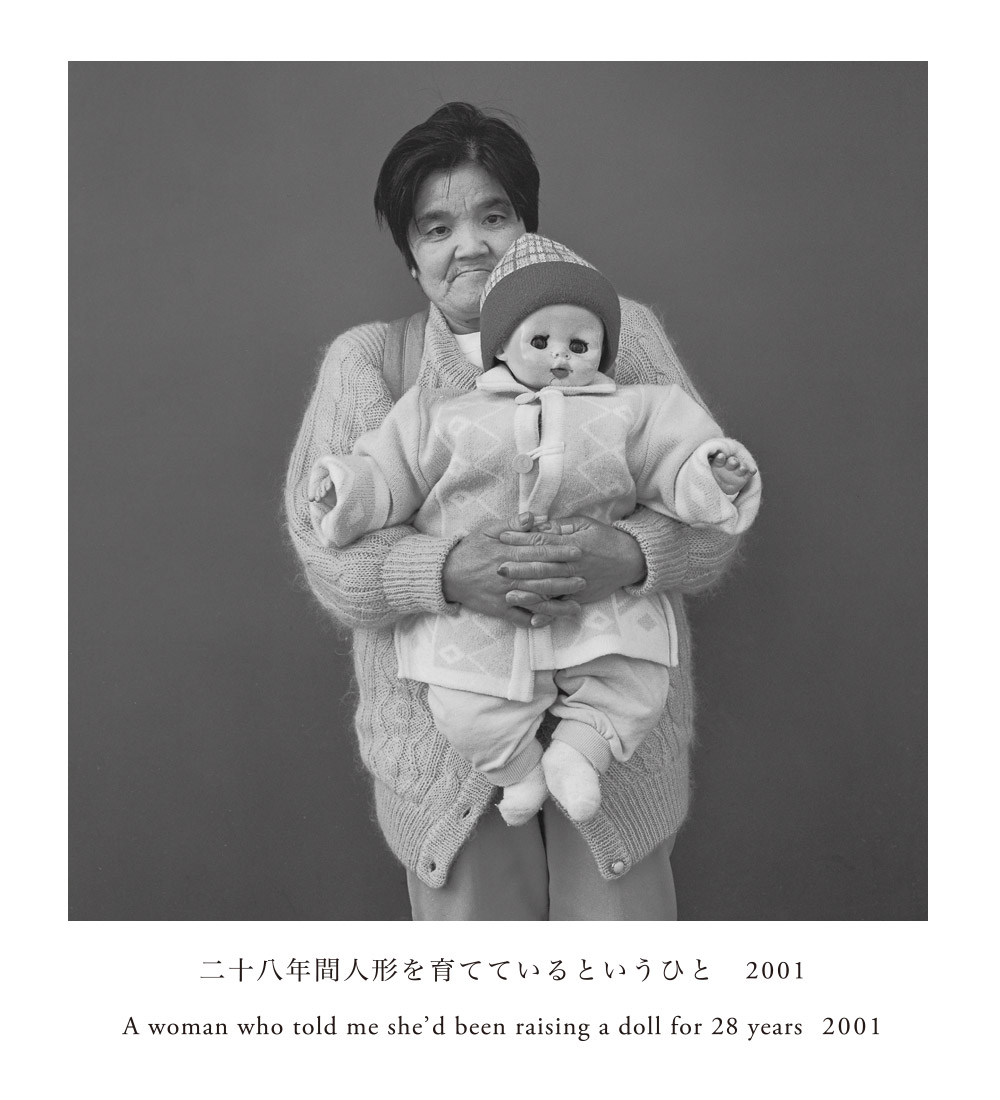

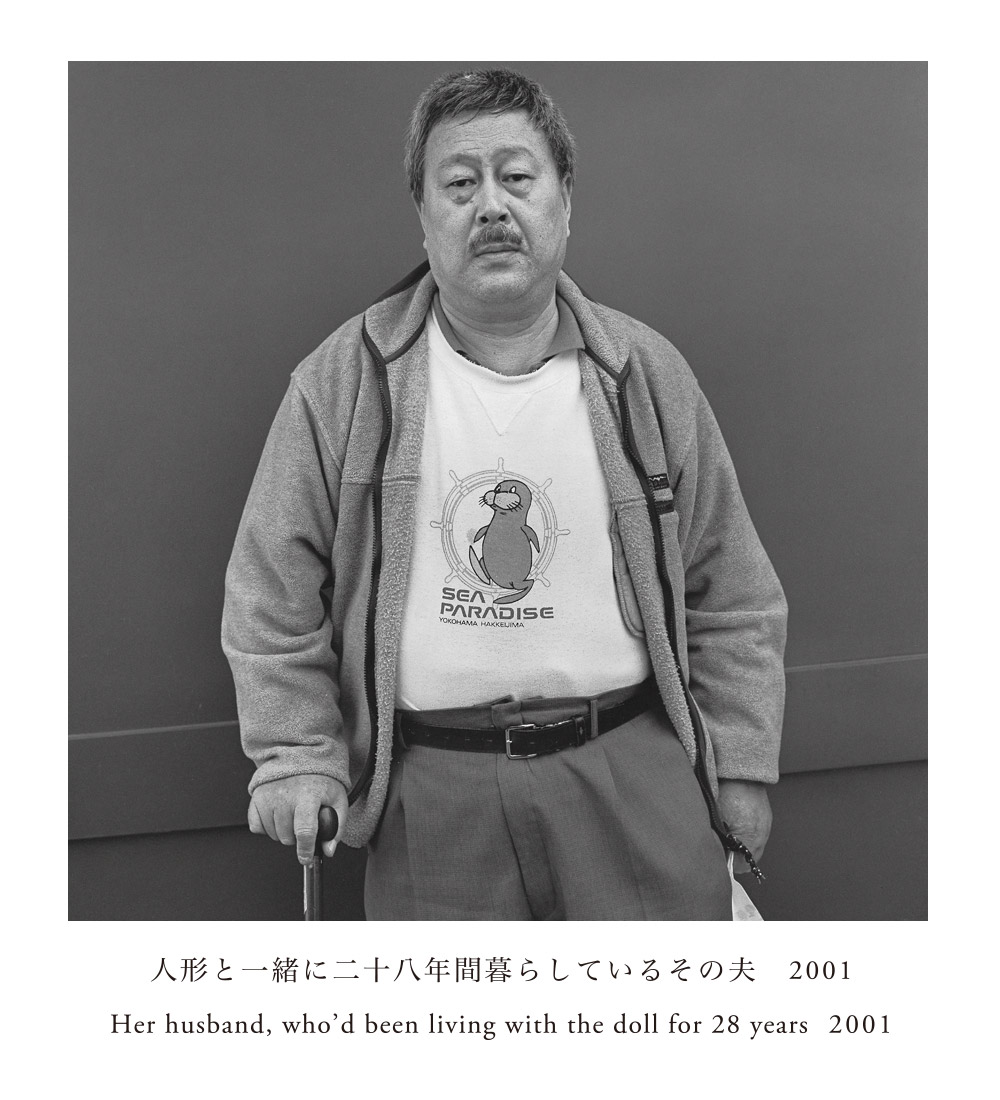

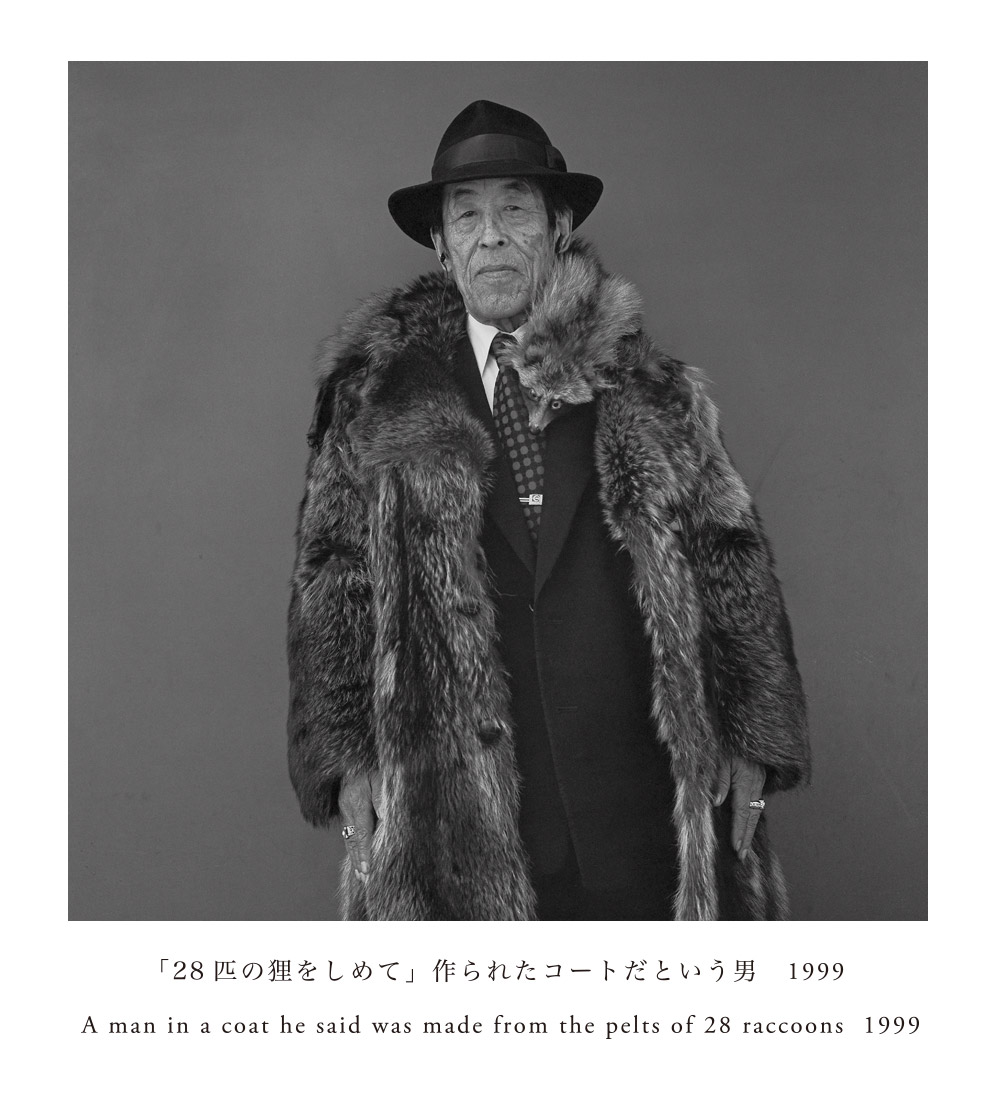

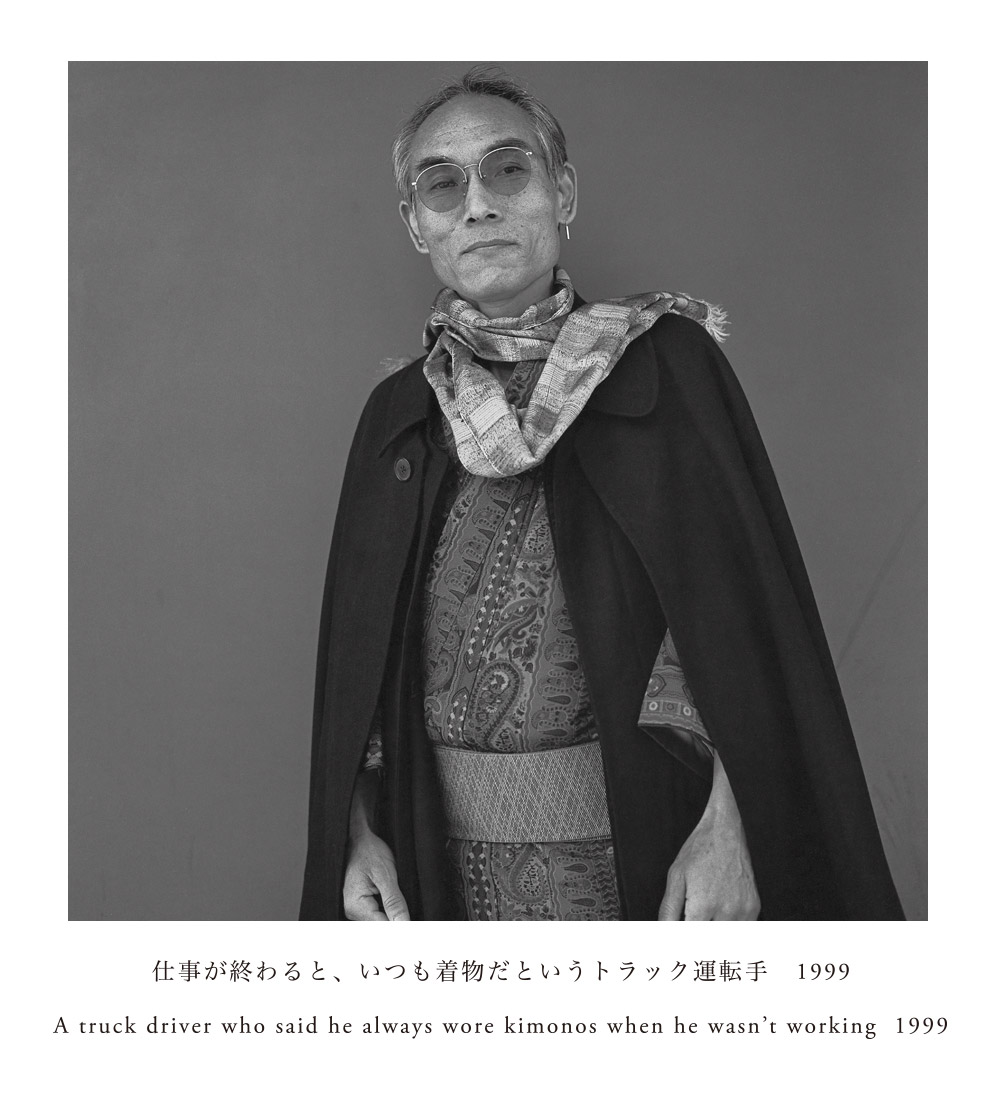

「どういう人を撮りたいと思うのかは、なかなか説明しにくいんですよね。人間とは何かっていうことの、うっすらとした手がかりになるような人です。単なる変わった人を撮るわけじゃない。海の底まで通じるような何かをもっていないと、写真がただの仮装行列になってしまいますから。ポートレイトにはその人の時間の蓄積がずーっと写っていないといけません。一過性だけで目をひくような、薄っぺらなものはポートレイトではないと思っています」

ー 立ち姿や服装もすごく「きまっている」人ばかりです。

「洋服はその人の“うろこ”のようになってないと駄目なんです。いかにも着せられたようなのではなくてね。汚い格好だとしても、その格好がその人の肌のようになっている。そういうのが、ファッショナブルなことだと思います。コム デ ギャルソンの1枚の黒布で作った服みたいに。あれはすごく格好いい。好きなんです。川久保玲さんの仕事が。高くて買えないですけれど(笑)。ポートレイトは目と顔が重要といいますが、それよりも肩の線とか腕の線とか、そういうことがすごく語り出すんですよね。それが人柄を表現するんです。撮る時は指示をすると不自然になってしまうから、『左足に体重をかけてください』と言う程度。表情がフリーズしてしまうので、カメラは手持ちでやっています」

ー なぜ浅草なのですか。

「私は浅草の人を撮りたいわけじゃないんです。浅草という限定された場所で錐(きり)をもむと、地球の裏側まで抜けていくっていう感じがあるんですよね。だから浅草というのは、私の触媒としての場所なんだと思っています。それがわからない人は、『こういう変わった人を撮りたければ、大阪に行ったり沖縄に行ったりしたら、もっと確率よく撮れる』と言う。でも、それは違います。ただのコレクションになってしまう。もっと本質的なものを求めてるんです。浅草という場所でずっと見ていると、そこから普遍的でインターナショナルなものが見えてくる。かもしれない」

ー 40年。なぜそんなに時間をかけて同じことを続けるのでしょう。

「優れた表現というのは、時代をまたいでも発信する力があります。私が死んだあとも、50年、60年と作品が残っていけばいいと思っていますが、それは私がいつか見返りを受けたいからではない。そのくらい長いスパンをもっていないと、私の写真としての表現が成り立たないように思うから。撮っているものがすぐ見返りを受けたら、すごく短いスパンでしか生きられません。飯を食えなくてもやるっていうことは、時代をこえる力を身につけることです。長い時間をまたぐことを、追い求めざるをえないんです」

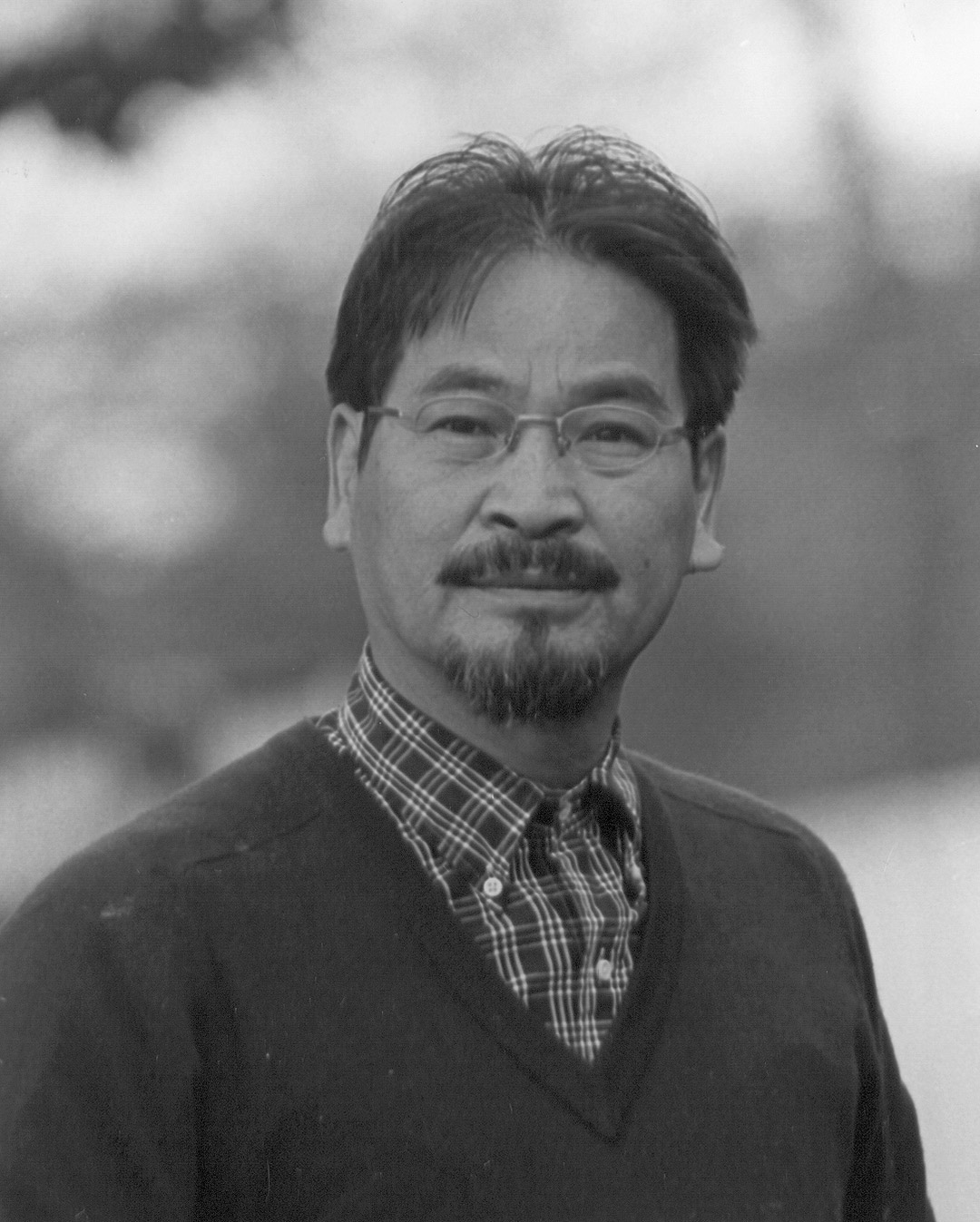

精悍な白髪の風貌が、その言葉をより重くする。しかし難しいことを選んで言っているわけではない。ただひとりでずっと写真と向き合いながら、写真家として自問を繰り返してきたからこその血が通った言葉。氷が溶けて薄まったアイスコーヒーを飲みながら、時折汗を拭っては、考えながら話す。これまで刊行された写真集のページをめくり、ひとつひとつの写真に触れながらそんな話を聞いていると、すっと腹に落ちてくる。そういうことなんだと思う。そしてこんなことを言った。

「写真は誰にでも撮れると思ったんですよね。でも何年か経って、何もそこに写らないことを知りました。だから私は写真家になれた」

それっぽく写っているようでいて何も写ってない写真か、モノクロームの壁を背にした人の何かが写っている写真か。カメラとレンズが魔法をかける。見えそうで見えない、聞こえそうで聞こえない、分かりそうで分からない。その「何か」とは何だ。ヒントはある。

「10年くらい前にポーランドで写真展をやった時、アンジェイ・ワイダさんが奥さんと一緒に来てくれました。2日も続けて。そして『これは全部日本人か?』と聞かれたんです。そうだ、と答えたら、彼はぽつりと言いました。『なんて我々と似ているんだ』とね」

浅草にいた東洋人と東欧人はもちろん似ていない。しかしモノクロームの写真になった時、ポーランド映画の巨匠には、同じに見えた。きっとそこには人間としての「何か」が写っている。鬼海弘雄が写真家であり続ける証の「何か」である。

全身で待ち続け、全力で撮り続けたポートレイトは1100人を超えた。未発表の人の写真もまだまだある。それでもきっと、今日も浅草か東京のどこかの街角で。あるいは遠くインドの夕暮れで。写真家はそれがやって来るのを静かに待っている。

On most days of a week, Kikai gets up with the sunrise and begins the day with a cup of his favorite tea. Sometimes he feeds his cat, too. After doing housework and taking a walk, he goes to a photo shoot around 10AM. What he puts in his backpack is a Hasselblad camera, an 80mm lens and some rolls of Brownie films. He walks to his nearest train station to catch a rapid train and then transfer to a subway to get to Asakusa. Soon after arriving at the historical town around 11AM, the time when most of the shops near Sensoji shrine open, he goes to a red wall that he always uses as a backdrop. If the wall got dirty, he wipes it before shooting. Then he begins to wait for his object to come in the shrine, looking at passersby.

With a little luck he could meet five-six people to photograph, but normally he takes only a few portraits a day. There are times, however, when he just waste three hours to stand there. Even if he found one, some people immediately refuse his enthusiastic offer or ignore it. As the situation demands, he is generous with altering his longtime habit. In the hottest time of summer he goes to Asakusa by the first train while he leaves home in the afternoon during winter to make a brief stop at a food stall to get warm meals. Or he may spend a great deal of time in big projects such as “Portrait of Tokyo” or “Candid Photos taken In India and Turkey” which he works in parallel with the portrait project in Asakusa. But yet most of his time has been spent on waiting ideal people in the town for forty years. Such tireless effort and vast amounts of hours do make the series of portraits maverick and impressive.

I feel sorry for him to ask this question because so many people may have done the same. But it’s difficult not to ask that.

ー What kind of people are you waiting for?

“It’s not easy to explain what kind of people I’d like to photograph. They may have to be a kind of clue for us to understand what a human being is. I don’t just photograph quirky people. They should have something very deep inside, otherwise the series of portraits will look like a fancy-dress parade. A portrait photo has to express the object’s lifelong history. Unabiding, flimsy ones shouldn’t be called portraits, I think.”

ー I found their figures and fashion really cool.

“Clothing should never be an imposed costume of the wearer but be something like their ‘scales.’ It has to look cool in photography even though it’s dirty in reality. I think that is what one should describe as fashionable, like a COMME des GARÇONS garment made from a black cloth. The piece looked really cool. I love what Rei Kawakubo has done although her clothes are too expensive to buy (laugh). It is said that merit of a portrait is determined by the object’s eyes and face, but I found that the shoulder line and arms are much more eloquent. When I photograph those people, I don’t give many directions as it makes the portrait rather artificial. I don’t use a tripod, too, because it hardens the object’s face.”

ー Why did you choose Asakusa?

“I don’t try to photograph people in Asakusa. I feel like as if I could burst through the earth by drilling down on the limited place. So, Asakusa is a place for me to be a catalyst, I think. People who can’t understand it tell me that I should go Osaka or Okinawa to photograph strange people more effectively. But that’s just a collection and far from what I wish. I want to have more essential things. As I keep looking in Asakusa, I can see something universal and international. Maybe.”

ー You have done it for forty years. What on earth spurred you to such a feat?

“Great works have ageless power to express something. I wish what I have made can remain for years, but that’s not because I want reward. That’s because I think my photography needs such a long period of time to be approved as photographic expression. If one could receive compensation soon after she/he releases her/his work, she/he may be able to live only a brief life. By doing things tirelessly even though it makes no money for you, you can get power to survive through the years. So I have compelling reasons to pursue things that needs great amounts of time.”

Kikai looked really sharp with gray hair and it added extra weight to his words. But what he said was not difficult at all. The words sounded credible because those were generated from his experience as a photographer. As I listened to him talking about each photo, I could naturally understand what he meant. And he said;

“I thought everyone could take a photo. Years later, however, I realized that nothing can be taken in a photo. That was the reason I could be a photographer.”

There are photos that captured nothing while his portraits depict “something” inside the objects as his camera and lens enchant it. Then what’s “something” in his photography? The answer is tantalizingly out of reach, but there is a clue.

“When I held an exhibition in Poland, Andrzej Wajda visited the venue with his wife for two days in a row. And he asked me if the people in my photos were all Japanese. After I told him yes, he quietly said; ‘How similar we are.’”

Of course Japanese in Asakusa and Eastern European people don’t look alike. In black and white photography, however, they look almost same for the Polish movie giant because there is “something” common to human beings. And it is “something” determines Kikai as a photographer.

Now the number of his Asakusa portraits becomes 1,100 pieces including tons of yet-to-be-released ones. The photographer is still waiting for his object. Today he may be standing in Asakusa, seeing people in Tokyo, or enjoying a sunset view in India.

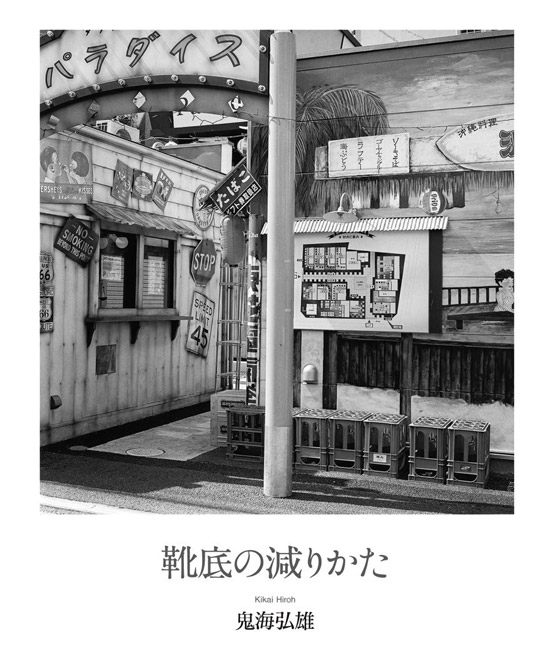

鬼海弘雄 HIROH KIKAI

1945年山形県寒河江市生まれ。法政大学文学部哲学科を卒業後、マグロ漁船の漁師見習い、暗室マンなどを経て写真家となる。以来、「浅草でのポートレイト」、「東京の街の肖像」、「インドやトルコでのスナップ」という3つの連作を続けている。2004年『PERSONA』で第23回土門拳賞を受賞。写真を掲載した浅草でのポートレイトは、『東京ポートレイト』(クレヴィス)、『ぺるそな』(草思社)、『世間のひと』(ちくま文庫)などで見ることができる。HIROH KIKAIBorn in Yamagata in 1945, Kikai studied philosophy at Hosei University. After experiencing to be an assistant fisherman of a tuna boat and a dark room staff, he became a photographer and started to make series of photography such as “Portrait of Tokyo” or “Candid Photos taken In India and Turkey” along with “Portraits in Asakusa.” In 2004, his work titled “PERSONA” received the 23rd Domon Ken Award.