Drinking Alone

ー How often do you go out to drink recently?

Kazuhiko Ota (Ota) : These days I travel a few times a month. Sometimes I have to go on a business trip once a week or so. Those trips were to research for magazine columns and to shoot TV programs. Therefore, I can have only one “alcohol free day” per week (laughs), though my doctor told me that I should have at least two such days a week. It’s a bit difficult to follow his advice but I try not to drink on Sundays as I do feel my age recently.

ー I’ve heard that you drink alone when researching. Is that right?

Ota : Most of the time I’m a solitary drinker. I used to go to research with a magazine editor and photographer, but they now often ask me to do it by myself because of a tight budget (laughs). Besides I can take a quick photo easily these days. I love drinking alone because I can immediately get focused on what I should do. If with company, I have to waste time caring about other people. On that occasion, I’m not at liberty to cut the research short (laughs). I go to an izakaya not to have a chat. I want to make my research more efficient.

ー How old were you when you began to visit izakaya?

Ota : I started to focus on izakaya just before I became 40. Though I began drinking much earlier, I used to go to posher places for drink to chat with admen and people in the same industry I was in. What I drunk then was whiskey with water and I ordered it as soon as I entered a pub. Then the hottest creative people of the time joined us one after the other. Such parties were so inspiring for me. I also attracted a bit of attention as a graphic designer at that time. I actually moved my place to the city center so that I could walk back home after drinking with them until late at night. I remember that interior designers were most powerful then. We had so many opening parties of edgy stores and bars designed by famous figures like Takashi Sugimoto and Shigeru Uchida. I used to design invitation cards for those parties. I don’t really remember who paid for our drinks. I guess my friends working for ad agencies did it for us. Anyway, I went those places to talk about our business, meet business friends and get business-related news. At that time, I didn’t mind what I drunk because it was not at the top of my list of priorities. But I got tired about such things after a little while and discovered the joy of solitary drinking. That’s how my life got off the track (laughs).

ー (Laughs) so where did you discover the joy of solitary drinking?

Ota : When I was working in Ginza, I went to Tokyo’s Tsukishima for the first time in my life. It is a town on the east side of Sumida River from Ginza, but I had never been there before. At the time Tsukishima was a good old place without the famous Monja Street. It was over thirty years ago. There were so many tiny old houses there and naked kids in the town enjoyed playing baseball in a vacant site. I was so surprised to know that we had such a place very close to Ginza, the most luxury area in Tokyo. Then I found an izakaya named Kishidaya in the town and walked into there just for fun. It all started like that.

ー Didn’t you feel awkward to go to an izakaya in such an unknown place?

Ota : I did a bit, but it was for fun. The izakaya was completely different from the stylish bars and pubs I used to go, totally anachronistic. Since then, I began to focus on izakaya. Kishidaya is still in business in Tsukishima. Although I once tried to revisit, more than ten people line up outside of the door even before it opened. So I gave up visiting there again.

ー What did you feel in Kishidaya at that time?

Ota : To put it simply, I felt that I didn’t have to talk. There was obviously no one to chat with as I went there by myself. As you may know, Kishidaya only has seats at the bar. It’s the place where construction workers go drinking after work. Nobody there wants to have a chat or sit face-to-face. No one gave me a whistle unlike people at a bar in a posh area. As I stepped into the izakaya, the master and other customers cast a quick glance at me without a word. That was all. Even the staff said almost nothing except when taking orders because they were too busy. The customers kept moistening their lips quietly in such a circumstance. The place was filled with manly atmosphere and completely different from the pubs at where we had parties with so many chats and card-exchanges.

ー I guess it was when Japan was in the end of the economic bubble.

Ota : Yes. And I noticed that silence made you a reflective thinker. At the beginning I pondered over my work, but after a while I ran out of things to think about. So I started to stare at an aluminum ashtray on the bar counter. The ashtray I saw at a posh bar looked stylish, but the one on Kishidaya’s counter was battered. I was working for the publicity department of Shiseido at that time, and people around me kept saying that newer was better. However, I thought that old stuff also looked adorable when I saw the ashtray. I wasn’t tired or became skeptical about what I did. It was the antiworld or counterculture of what I believed. I discovered a different world view. Nowadays, the value of outdatedness has been leaped, though.

ー You realized a totally different value then.

Ota : I did. I found something new whenever I ordered a dish there. Everything at the izakaya was detached from any trends. I then realized a value of being frank and straight. But I didn’t want to bring my business friends there even after becoming obsessed with izakaya. I knew they would laugh at the atmosphere. Maybe I was so generous that I didn’t insult such an anachronistic way of life even working at a super elegant company like Shiseido (laughs). Or, maybe I just have a natural inclination for loving it (laughs).

ー That was how you started to go drinking alone.

Ota : I worked as a designer by day, creating something modern and fashionable. But I spent my night at a cheap old izakaya, being steeped in nostalgia. By doing so, I could restore a mental balance. Besides the local sake boom was occurred around that time. Famous local sake such as Koshino-kanbai became available in Tokyo and I was drawn into daintiness and diversity of the traditional beverage. So I organized “Izakaya Kenkyukai (the Society for Izakaya Research)” with my friends. But what we did mainly was to go out for a drink together (laughs). We then tasted sake and snacks while discovering the comfort of izakaya. We also did some thinking about why izakaya made us so comfortable.

ー Wow you finally began researching.

Ota : Yes, finally (laughs). I was so keen on the activity that I put out some newsletters. I’ve loved to make a newspaper sine I was a kid. The paper I made as a child was named “Sports Times” (laughs). I can still draw the logo. My father saw it and said “Oh.” When I was a junior-high-school boy, I made a wall newspaper daily. All the articles on the paper were written by hand. I even conducted investigating reporting, examining the number of broken windows at my school (laughs). Makoto Shina, a Japanese author, said he also became an editor in chief of a wall paper at the age of ten, and later started to publish a mimeographed newsletter for a club, making eleven copies per issue. When he showed me an edition of the paper, I felt honor to know that he shared the same interest as me. I then created a saying ; a newspaper issuing more than two copies is a mass medium, while the one issuing just a copy is a diary. He later asked me to design his newspaper-like serial article. I recently learned that Tatsuru Uchida also used to publish a personal newspaper when he was a school kid. So, there are quite a few people who had put out newspapers in their childhood.

ー Did you want to convey the fascination of izakaya through those papers?

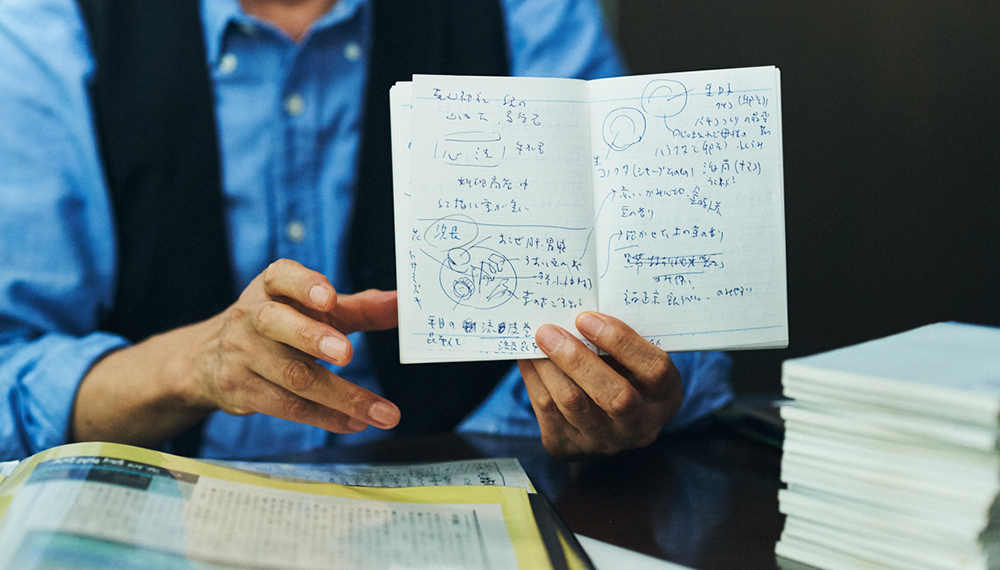

Ota : No, no. I’ll show you. (And he stood up.).

ー Oh thank you. It’s covered in handwriting.

Ota : I didn’t have a PC then, so writing by hand was much faster. I was good at writing fictional round-table talks with lots of jokes. I also put some detailed charts. As I sent the paper “Izakaya Kenkyukai Quarterly” to the members, Makoto Shina got hooked on it and became the first non-member subscriber (laughs).

ー How long did you make the paper?

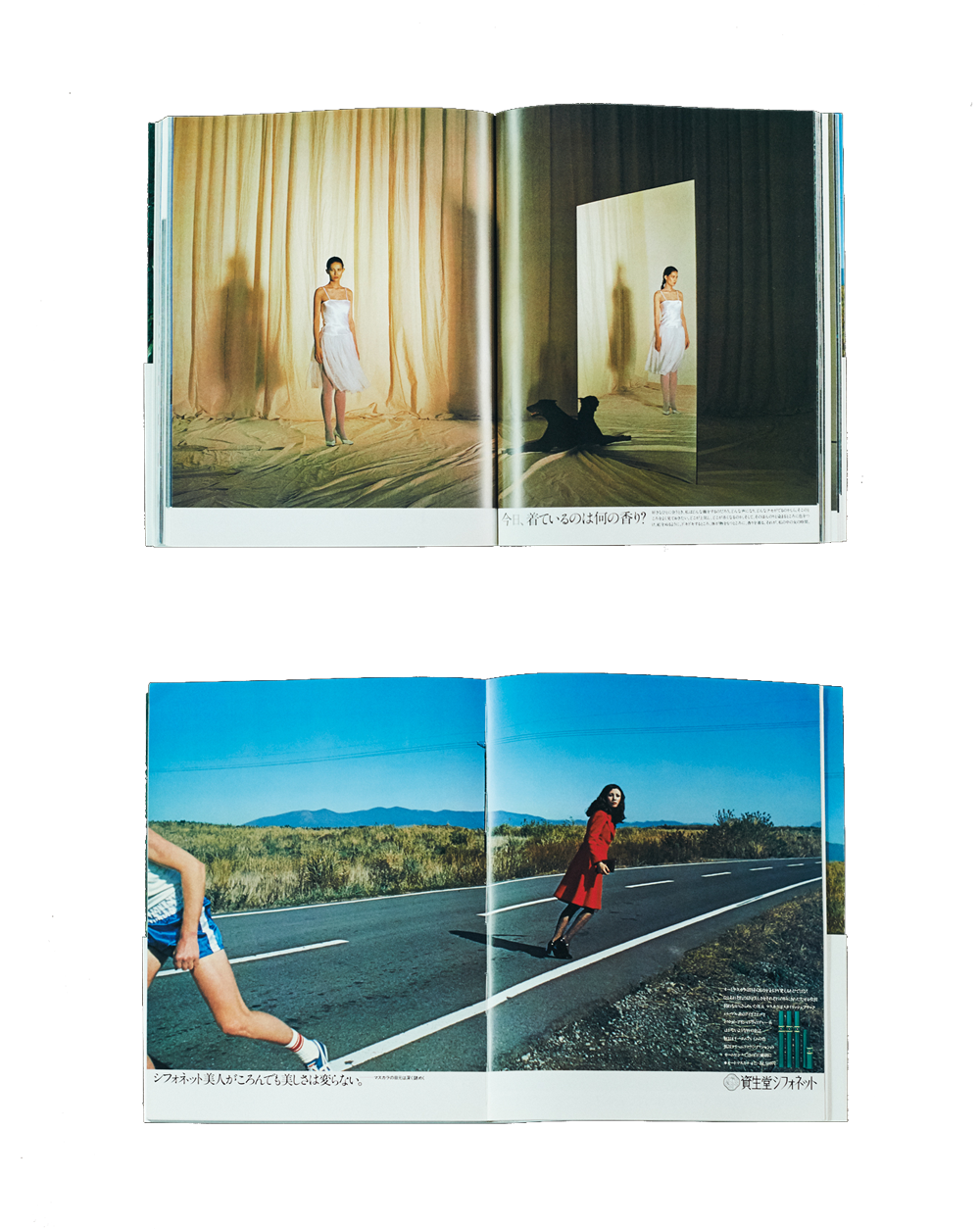

Ota : Let me see. (And he opened a folder.) It was first published in December 1987 and the last issue was made in June 1990, featuring Tataki (lightly roasted fish) and cold sake as its main topic. When I was making these newsletters, a magazine called Days Japan was launched by Kodansha and the editor of the magazine contacted me. So I met with him and showed him my work in the hope of getting some free drinks. To my surprise, he read it thoroughly and asked me to make same stuff for the magazine in serial form. Since the paper was just a private newsletter, I couldn’t do the same for my magazine article. Instead, I wrote the article in the style of column with good izakaya information, a fictional round-table talk and charts. At that time, I believed that I could put everything in the world into the form of a chart. So I enjoyed making it. For example, I graphically showed how to discriminate good izakaya and how people get drunk. It was exciting to see what I had made all by myself in a magazine. I think I was not so busy at that time as I kept putting out the paper for Izakaya Kenkyukai in parallel with the column. I used to publish a personal joke paper at Shiseido, too. When I was involved in Shina’s movie shooting, I made a communication and publicity paper for the staff as the project’s PR person. I guess it was a bit better than other papers I made because people released a book about it. So, publishing a newspaper is not a hard thing to do for me.

Feelings for Izakaya

ー Then, what is your definition of a good izakaya?

Ota : Izakaya Kenkyukai had establised “the Three Basic Principles of Good Izakaya” at the very beginning. According to the principles, a good izakaya had to have good staff, good drinks and good food all at once in a fine balance. Later we revised it and added one more principle, a good history, because a good izakaya should have some stories to tell unlike new and flashy bars. The best izakaya should meet all the principles above.

ー You may also have your own decorum which you think people should observe at izakaya. I’ve heard that you always visit izakaya soon after it opens.

Ota : Oh it’s just because I want to get a drink as soon as possible (laughs). And people in the service industry always welcome their first customer of the day because they would become anxious if there is no customer an hour after opening. They may feel relieved as someone walks into, thinking “Now I can start the day.” I want my favorite izakaya do well, so I’d like to be such a lucky customer, even though nobody has ever asked me to do so (laughs). Moreover, the air is fresher and cleaner if you visit izakaya right after opening. I like it.

ー Do you have any other drinking methods?

Ota : You can learn local drinking methods as you see other customers in various izakaya. Drinking alcohol exposes your true colors. What is good about izakaya is that men always show themselves there. That’s what you should watch it at an izakaya. There are some men who get drunk so badly at a cheap izakaya, but assume a gentlemanly attitude at a decent restaurant. And the former is his real self. Watch people’s character more carefully at a casual pub like an izakaya. I cannot be a role model, though (laughs). I just want to keep it in mind. Female customers pay more attention to such behavior, so be careful.

ー I think you have learned many things while visiting a number of izakaya. Since you go there for research, you may observe other customers more carefully than us.

Ota : After I published my first book, “Izakaya Taizen,” based on the serial column on izakaya for Days Japan, an editor of Shukan Shincho magazine asked me to write an izakaya travelogue, saying; “You can go anywhere for research and write anything you want.” So I went for a three-day trip to Osaka and wrote forty pages about izakaya there. The editor was so surprised and said he didn’t expect that much.

ー Forty pages for the first article!

Ota : Because they said I could write as much as I wanted (laughs). Anyway they loved it and let me do the same once a year. After three years or so, they asked me to start a serial article. I now think Shinchosha, one of Japan’s major literary publishers, tested me then whether I could write properly. What they expected me to do was to follow their theme, volume, deadline and standard. Although I didn’t realize it at that time, I’m now sure that they tested me. Then I began to travel around the country on a monthly basis to find good izakaya and write about it on a full scale.

ー I guess it’s a quite hard thing to do.

Ota : After started the column, I realized the fact that I had to find a nice izakaya in a town I had never visited before. If I couldn’t find any, I had to trot around the town late at night, looking for izakaya signs. Though people loved to read a story about a crap izakaya, it was against the rule to mention the names of such izakaya in the article. Even if I made it obscure, local people could tell it anyway. Since the column was quite long, I wanted to conclude it with a happy ending, telling nice things about the place I visited. I knew it was crucial for a serial column.

ー It’s surprising that you sometimes couldn’t find an izakaya to write.

Ota : I felt a sense of defeat when I had to revisit the first izakaya I went on the same day. In that case, however, the fact that I had no other options made my eyes more watchful. And then I stirred myself to write a column on the izakaya as a professional columnist even if things they offer were not worth doing so. On the following day, I often visited such an izakaya again because I knew there was no better place anyway. Then I got a warm reception from the owner with a slightly bigger voice and grin. In that sort of case, the owner often gave me information of other izakaya in the town. So it is always important to walk into a place in a risk-taking attitude.

ー And you didn’t have the Internet at that time.

Ota : There was no internet and no izakaya guide. But I was proud of doing such a truly unexplored thing, thinking that it seems like there was no one before me who had done it. Anyway, my one-year contract with the Shukan Shincho was extended for three years in the end. I was so excited to travel around Japan to meet good food and drinks during my first year. You can see it in my writing. In the second year, I got more relaxed and began to pay more attention to the environment, history or relationship of each izakaya. With a bit of breathing room, I could even hear other customers’ conversations. After getting into my third year, curious to say, I became more introspective. I sometimes wondered why I loved traditional izakaya so much. Also nostalgia made my writing more like internal monologue. You may realize that what I wrote in my first year is totally different from the articles in my last year. The latter is so settled. I think that is because I wrote each piece sincerely according to my emotions. I was so glad when Hiromi Kawakami told me that she had read my column for the very first thing. The trilogy, “Nippon Izakaya Horoki,” is definitely my debut work.

ー So there was a great change in the article.

Ota : Though I say it myself, my writing skills had developed dramatically while I could also make personal progress. I wrote about thirty pages for each column because the length was crucial. Other writers ask me once in a while about how I write it. I then tell them to write six pages about one izakaya to begin with, but even that seems hard for them.

ー I think it is really difficult to write so long about one izakaya. But it’s possible for you even the time you spend at each izakaya is just a single evening, right? Maybe your observation skill had also been developed during the period.

Ota : What I do hasn’t changed since I playfully published the newspapers for Izakaya Kenkyukai. I’ve been trying to find out the source of goodness of izakaya. What I want to write is not a food-spotting column, but about the look and customers of a izakaya.

ー Do you have tips to research izakaya?

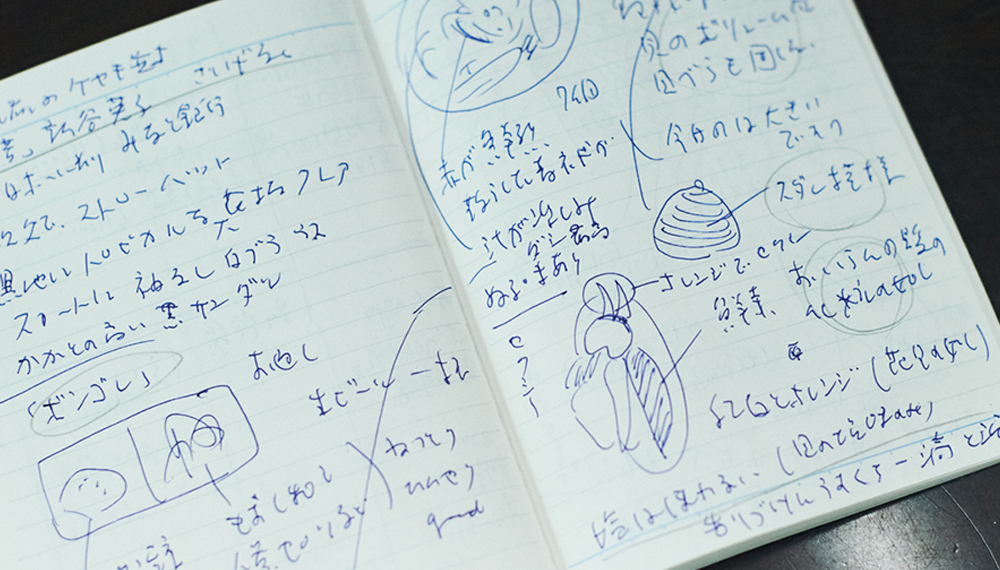

Ota : Making notes is the only thing you have to do for research. Since I always spend a long time to research, it’s almost impossible to remember what I order. You can’t tell all the dishes you had at an izakaya day before yesterday, can you? So I take a good note about everything I see and hear at an izakaya. What I jot down is similar to a journalist’s and based on the Six Ws. Numbers and names are above everything else. I note down a name of dish strictly word for word. And doodle sketches are also essential for my research. Although I once tried to take snaps instead, it couldn’t be the replacement because I couldn’t remember the point I want to highlight. If I doodle, however, I can edit it as I like to make the point clearer. Being a graphic designer, doodling and editing are all in my line. When taking the note, I also choose words to describe taste of food and write it down. So that I can recall the taste later. As I complete the note, my column is almost half-done.

ー You have improved the note-taking technique with repetition, I guess.

Ota : However, taking notes on a bar counter does look suspicious. Izakaya staff may ask me; “Are you from the tax office?” (laughs) When they shoot a nervous glance at me, I show them my doodle. If I tell that I just love drawing food illustrations, they often say nice things about it and lose interest. Then nobody cares about me even when I copy the izakaya menu or mark down that the hostess is beautiful. But the biggest drawback to make a note is my handwriting. It becomes unreadable as I get drunk (laughs).

ー Your handwriting gets drunk, too (laughs).

Ota : That’s right. But oddly enough, I can somehow read it in the end (laughs). So, for me, losing my notebook is much worse than losing my wallet. Actually I have once lost it. I became aware that I had left my notebook at the first izakaya of the day when I went to the second one. Then I ran back into the first izakaya and the owner waved my notebook at me. I felt really embarrassed. I’m sure he looked inside. Since then I always check my belongings - my wallet, glasses and notebook - when leaving an izakaya.

ー Is there any reason why you always use this A6 notebook to make a note?

Ota : It’s small and handy. At an izakaya, you can slip it under your legs. I quickly pull it out when taking a note and put it away after finishing. If I want to make a long note, I do it in a bathroom. My uncle who used to be a journalist taught me those things, saying that I have to finish everything on site. You cannot call the izakaya later to ask about details you forget. Izakaya is always too busy to answer such phone calls, and often refuse a research or interview. So I have to finish everything on site. A detailed note is essential to write a long and well-structured column. I read many food essays before writing about izakaya, but there were almost no long specific ones. If you are an established author like Shotaro Ikenami or Hitomi Yamaguchi, you can conclude your column with simple words like; “it was good.” But a nameless writer like me has to make it more detailed and copious. I’ve always had it in mind from the very beginning. My columns had to be practical.

ー Now I understand how your tasteful columns with specific information have been created. There are quite a few people who love your work so much that they travel around Japan to visit izakaya by themselves.

Ota : Yes. I feel flattered when izakaya owners tell me that there are many customers who come to the place because of my columns. However, I started to consider myself a professional writer only in the past five years or so. Before then, I thought people found my writings a bit interesting just because those were written by a graphic designer. I therefore introduced myself as a graphic designer / izakaya critic at that time. Well but I impudently call myself as “an author” recently (laughs).

Talking about His Personal Hisotry

ー You have mentioned earlier on a professional. Were you born to a family of artisans?

Ota : My father’s family had been a metalsmith for five generations and made small metal parts of traditional furniture in Nagano Prefecture. Although my grandfather had inherited the family business, he didn’t make his eldest son, my father, do the same, saying that education was more important. So my father became a teacher. But my grandfather’s professionalism as a skilled artisan attracted me. In a book which my father wrote in his later days, he described himself as “an artisan of education.” I then thought that we were definitely descended from an artisanal family.

ー You have your artisanal ancestors’ blood in your veins.

Ota : Being an artisan means being professional. And being professional means living by getting paid for performing your duty perfectly and punctually beyond expectation. My father told me that my grandfather once undertook a difficult task of making custom-ordered metal parts with delicate artwork for marriage furniture. Many other metalsmiths had declined the order as it was too challenging. My grandfather also thought it was a pain, but didn’t want tell it to the client. So he asked a prohibitive price for the job instead of just turning away the order. However, the client generously accepted the price and my grandfather had to accept the order. At other times, another client asked my grandfather if he could get a discount even though he was satisfied with the quality of products. After hearing that, my grandfather slapped the products without a word. It was the pride of an artisan. I’ve also heard that he used to leave work early to go for a drink. There was something artistic about him as he had a license for teaching Japanese flower arrangement. I think I have inherited the taste from him.

ー You inherited such artisanal pride, too.

Ota : I think so. When I was a busy graphic designer, my friends asked me to hold a group exhibition with them, lifting all the restrictions on design we normally had. But I was not interested in doing it at all. Graphic design is different from drawing or painting. We have to have a client to do it and it is actually the most amusing part of design. It’s definitely not a matter of money - I think like that just because I am a creative artisan. I’d like to show my ability by doing so.

ー Have you liked to make something since you were a child?

Ota : Yes, because I couldn’t do other than that. I wasn’t good at math and sports. Even though I once thought of doing something practical, I knew nothing to work on a farm. So I decided to get a job in the world of design.

ー You moved to Tokyo when entering a university.

Ota : Around that time, I had the specific goal of being a professional graphic designer in mind. As the world of graphic design didn’t seem to have an apprentice system, I decided to study at a university in Tokyo. Later, when I myself taught at a university, I always asked the same thing to students in the first place. The question was; “What is the most important thing to be a designer?” The answers from my students were like “novelty” or “to be unique,” and they showed unsatisfied looks on their faces when I said the answer was “deadlines and measurements.” But you can’t be a designer if you miss deadlines or make designs to the wrong measurements. Therefore, I kept telling them that a so-so piece finished on time is better than a great design made after a few days’ delay. That’s what a professional designer need to do.

ー Did you build such a professional attitude during your time in Shiseido?

Ota : I strongly felt the need to have that in mind after entering the company. People at work always told me about it and I also realized that I would get a printing company in trouble if I missed a deadline while working for Shiseido. As every professional designer knows, no one would offer a job to a designer who ignores a deadline and gets measurements wrong. We have to design even though we don’t feel like doing it. This principle has helped me a lot after I started writing. I always meet a deadline.

ー I think you got a lot of inspirations from the experience as a Shiseido designer.

Ota : That’s because there were many famous senior designers at the company including Hideaki Murase, Eiko Ishioka and Masayoshi Nakajo. I drunk with Nakajo just days ago and he looked stylish as always though his clothes were not from prominent brands. I become eager to be like him whenever I meet him, but it’s almost impossible.

ー Did he look smart when he worked at Shiseido?

Ota : Actually I didn’t work with him at Shiseido because he resigned just two years after joining the company. As he later began to design a magazine called “Hanatsubaki” for the firm, however, he often took me out for a drink. He is really a friendly man though what he says is always quite difficult to understand as his ideas are extremely unique (laughs). I admire everything he has designed. He says he now uses only red and blue for design. I think it’s so fascinating and feel the urge to do the same (laughs).

ー Do you think such an experience as a designer and writing about izakaya influence one another?

Ota : I had thought that those had nothing to do with each other, but now I feel that there is something in common between those in terms of creative work. As the word design means “to aim,” I have a purpose in my writing. And the same can be said for my design. I’m not interested in Sunday drawings or personal blog articles. Creative work has to be shown on mass media because that is the purpose of making it. I have had this idea since I made newspapers as a kid (laughs). Moreover, I always try to keep quality of my work as high as people required at Shiseido. I see modernism and nostalgia from the same aesthetic point of view. Well, I know it sounds like an exaggeration (laughs).

ー Designing edgy things and writing about dated stuff. It seems hard to do both at the same time.

Ota : It’s more fun. I can also refresh myself by doing so. But I don’t design much recently as I’ve been busy writing.

Now and the Future

ー What kind of style do you like? You looked really nice in a shirt with sweetfish pattern on a book called “Minna Sakaba de Okiku Natta (Everyone Has Grown up with Bars).”

Ota : It’s from Patagonia and I bought it a long time ago at an outdoor gear store. Seeing me watching it, the store staff came to me and said; “The item is produced only in this year, so you would look so cool if you buy this now and wear three years later.” And I still wear it after ten years have passed since then. I love the shirt that much.

ー I often see you wearing a printed shirt on TV.

Ota : Those are only clothes I have (laughs). I seldom buy clothes because I’m not interested in it. Even if I have money for clothes, I’d rather use it on drinking. It’s been always the most urgent and crucial thing for me. As you drink, you can enhance your relationship, make close friends and meet a person to look up to. It enriches your personality, too. Although I couldn’t meet a romantic partner and sometimes felt frustrated, I have had so much fun through drinking. I know young people need to be fashionable to show off, but I think girls prefer boys who can drink neatly at their favorite izakaya. Men should earn respect of others at izakaya and publish newspapers (laughs).

ー (Laughs) you said you love outdoor activities. Do you still do it?

Ota : I haven’t climbed mountains for a while. I seriously started it in my mid-thirties. I joined a mountaineering club and did even competitive climbing and rock-climbing.

ー How did you start it?

Ota : My aunt encouraged me to do it, saying there are many other inspiring things than just sitting at a desk or drinking at izakaya. I then got crazy about it. It was the time when America’s free climbing (a form of rock climbing without any equipment) was first introduced to Japan and I became caught up in it after taking some courses. Bouldering is an extension of the style. With the method, I climbed high walls in Mt. Tanigawa and Mt. Hodaka. I tried so many types of climbing including ice climbing. When I climbed the Eiger, I took two weeks of vacation. It was my longest climbing trip ever. I also enjoyed outdoor living as a junior member of Makoto Shina’s “Odd Expedition Team.” We went to a deserted island together while camping after river-rafting. It was so fun. I think my life was in its greatest years at the time. Camping has been my regular event and I still enjoy it with my former university students. We have around 30 people every time. The best sake in the world is definitely the one you drink at a camping site.

ー So you had expanded the range of activities from your mid- to late-thirties.

Ota : When a man reaches the age of 35, his work often settles down. In other words, it’s the time to look back the way he came. After having worked for Shiseido for a long time, I wanted to think about my own life. Mountaineering was perfect activity for me at that time because I didn’t think about design when climbing a rock. If I do, I fall (laughs). So it was great experience for me to ponder, getting away from my work. As my former university student invited me, I climbed a mountain last year for the first time in years. And, sadly, I felt my age (laughs). But I still love mountain climbing. I wish I could do it as soon as tomorrow.

ー Do you feel your age also when traveling around Japan and visiting many izakaya in one night?

Ota : I do. I can’t visit four-five pubs in a night now. When I started my first column, I was really ambitious and willing to research until the last pub in the town closed. I cannot do it now. When researching for my new book, I tried to visit at least two izakaya a night at the beginning. But I began to feel that my ability to evaluate an izakaya becomes less accurate as I get tired. So I decided to visit only one izakaya a night. When I go drinking with my friends, however, I can go as many pubs as I want (laughs) because it’s not for research. I can’t remember how many izakaya I went with Nakajo. Now I enjoy revisiting izakaya I have researched before in a more relaxed way.

ー More than thirty years have passed since you established Izakaya Kenkyukai and began to research izakaya around the country. Do you think izakaya has changed?

Ota : There are some changes, but I realize that every izakaya has an unchangeable “pillar” in it, too. I wrote about it in this book (“Nippon no Izakaya [Japanese Izakaya]”). As Izakaya had changed as a type of business, I begin to recognize the importance of things that never change. As you get older, you place more value on unchangeable things. It may sound a bit exaggerated, but those things can be called as “culture,” ordinary people’s culture. I professedly call myself “Tsuneichi Miyamoto of izakaya” (laughs).

ー Do you mean that izakaya staff and customers haven’t changed?

Ota : I meant that those people’s mind hasn’t changed. Having visited many izakaya around Japan, I realized that people in Hokkaido have something in common with Okinawa people while Akita and Kochi have completely different characters. I have read some books about local characters in Japan, but most of those are based on some bureaucratic figures and population distribution maps and totally different from what I’ve seen at izakaya. That’s the reason I decided to write a book about it. Through the book, I wanted to show that there are prefectural characters which can be seen only at local izakaya.

ー You can see those things because you’ve written on izakaya for a long time.

Ota : My thirty years of experience as an izakaya writer showed me what I couldn’t see before. You can’t write about it in an assertive way without a certain amount of experience and accumulation. I think I could be a professional and experienced izakaya writer only because I frequented there and took lots of notes about it. My passion for creating something made me do it for a long time. I always concentrate on one thing to improve the quality. Maybe I’m a bit pesky.