His Talent to “Love”

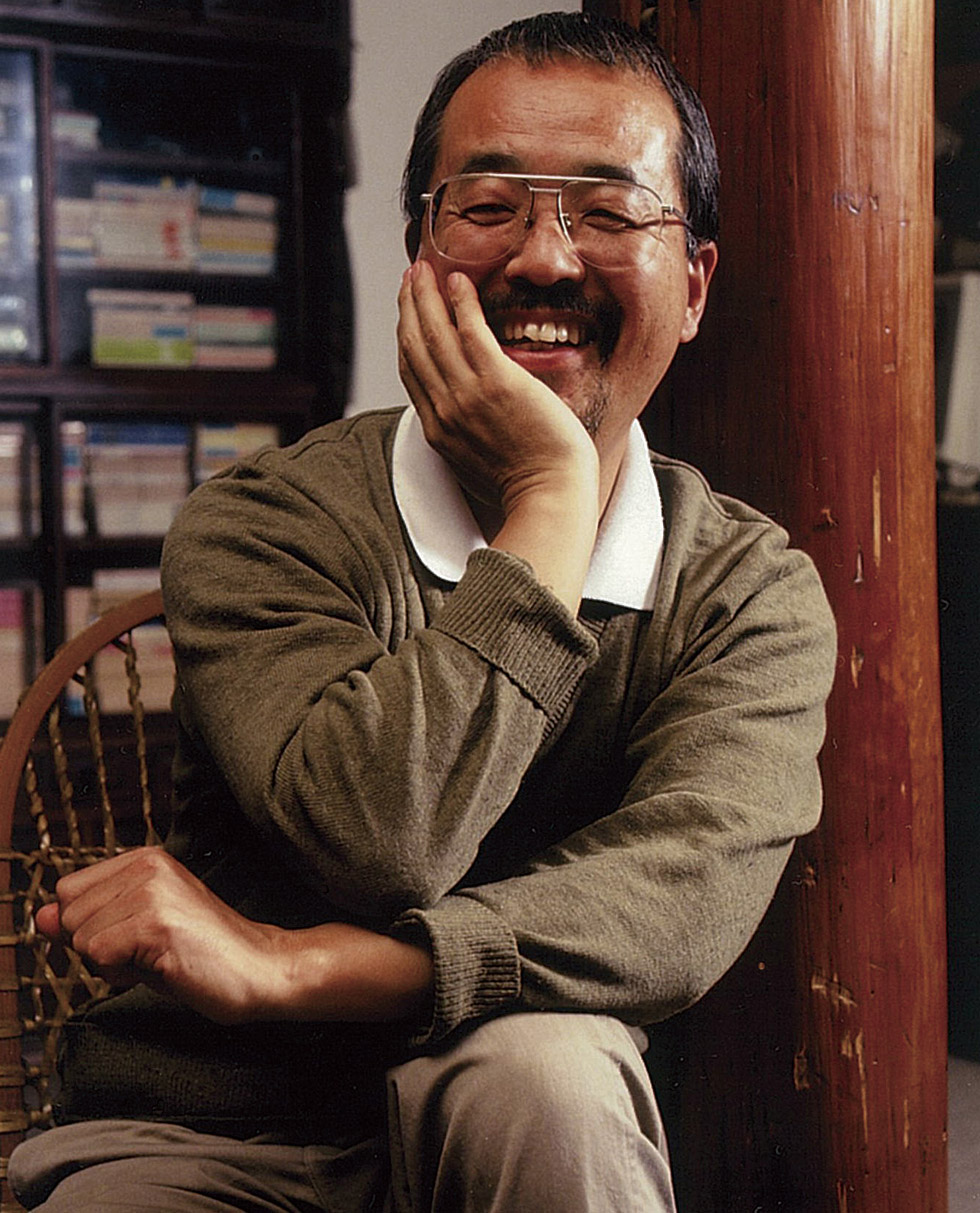

Born in Kazikazawa Town in Yamanashi Prefecture in 1938, Ashizawa moved to Tokyo at the age of 17 to study both at Faculty of Letters of Waseda University and Tokyo College of Photography. While designing a photography magazine, he took photos at Yokosuka Naval Base, showing something of his genius as a photographer. In 1960, he became a freelance graphic designer soon after graduating Waseda University and started to design various magazines such as Men’s Club and Heibon Punch after a while. He met Sachiko, a new editor of Kobunsha, in the same year and the two got married two years later. Ashizawa was lucky enough to develop his career at such an early age and to find the right woman at the same time.

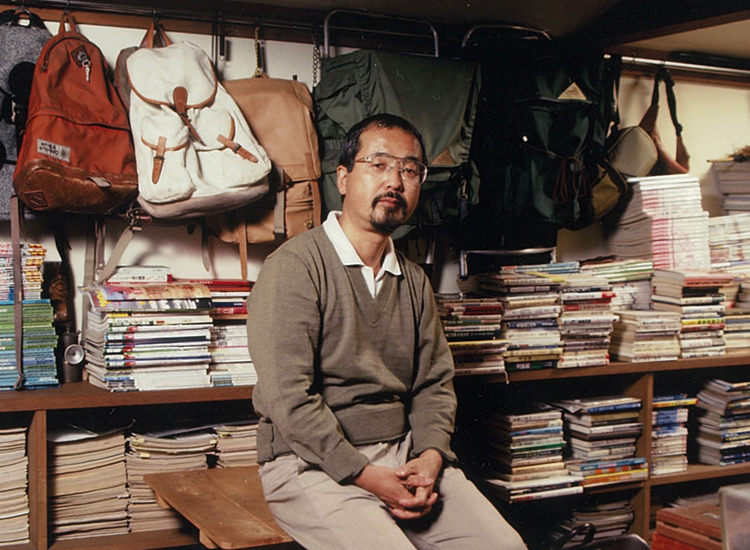

It was really hard to work in the magazine industry at that time. People repeatedly came in and out while phone kept ringing. Although editors continuously passed their writings to Ashizawa to design, he never became upset. Instead, he quickly sat at his desk and worked silently. After 50-80 pages of design were completed, he again left his desk quickly. There were always some books of beatniks and English authors on his desk despite the tremendous workload. As soon as finding some spare time, he began reading those books. Or, if he felt like, he just went out. “He was in the middle of a mass medium at the beginning. I think it was really exhausting, so going out was probably the way he handled stress. He might think about doing fishing again, walking mountain or going somewhere with a camera. Ashizawa originally wanted to be a photographer, but he might find something seemed more interesting - American nature and literature - when he strolled like that,” Sachiko said, looking back on Ashizawa then. In 1973, he began designing the cover of Yama to Keikoku magazine. His life as a graphic designer became extremely hectic.

His First Visit to Alaska with Sachiko

the first time. After having visited Australia, Wyoming, Montana and Oregon solo, Ashizawa decided to go to Alaska with his wife. “He told me that I should go there with him. We are traveled with two other married couples, Masaaki Nishiki (*1) and his wife as well as an editor of Heibon Punch and his spouse.” It was a fishing trip to enjoy magnificent nature of Alaska and supposed to be a fruitful for all the couples. “It wasn’t like that (laughs). I felt a cultural gap when I saw my meal was roughly served in a basin-like bowl. It looked like food for animals. Because the primary purpose of the trip was river-rafting on a rubber raft, we had to camp every day. In the course of the trip, however, we lost most of the food we brought as a raft belonged to our guide went down. After the incident, we ate fish we caught while camping. We could call for help if we wanted, but we decided to continue the rafting trip somehow on our own. We could manage to go on for ten days, utilizing all the food left. We must look miserable as we didn’t even change our clothes during the trip. I could get strong nerves in the end (laughs),” said Sachiko. Although Ashizawa started to introduce himself as an “outdoor writer” about two years before the trip, he gradually got writing jobs related to outdoor living right after the outstanding experience in Alaska.

Now I would like to note that there was neither the word “outdoor” nor the idea of “outdoor living” in Japan at that time. The history of “outdoor living” began in America when people in the country experienced a dramatic change in their lifestyle. Soon after the rise of beatnik culture in the beginning of the 1960s, the hippie movement started in the country followed by the end of the Vietnam War. Without the brunt of criticism - the social system, war, morality and materialism - young people started to pack their belongings and left cities to live a lives based on conservationism and ecological thoughts. It was how the idea of “outdoor living” emerged. Though it sounds similar to “outdoor sports,” what those words indicate was totally different. “Outdoor sports” were considered as a kind of professional outdoor activities which required people to use specific equipment. Ashizawa is a man who introduced the idea of “outdoor living” to Japan with the keyword “outdoor.” At just about the same time, Yasuhiko Kobayashi, a Japanese illustrator who maintained close relations with Ashizawa, began to use the word “heavy-duty” in Men’s Club magazine although the word had originally been used for the description of outdoor sports gear. Since then American outdoor clothing and gear became widely accepted as a style of fashion with backing from the publication of two influential books, “Made in USA Catalog” and “Heavy-duty no Hon (The Book of Heavy Duty),” as well as the launch of POPEYE in 1976. However, “outdoor writer” Ashizawa had never got into the world of fashion. What he focused on was outdoor-oriented lifestyle which was originated from beatnik and hippie culture, as well as the idea of facing nature.

The Encounter with Morio Sato

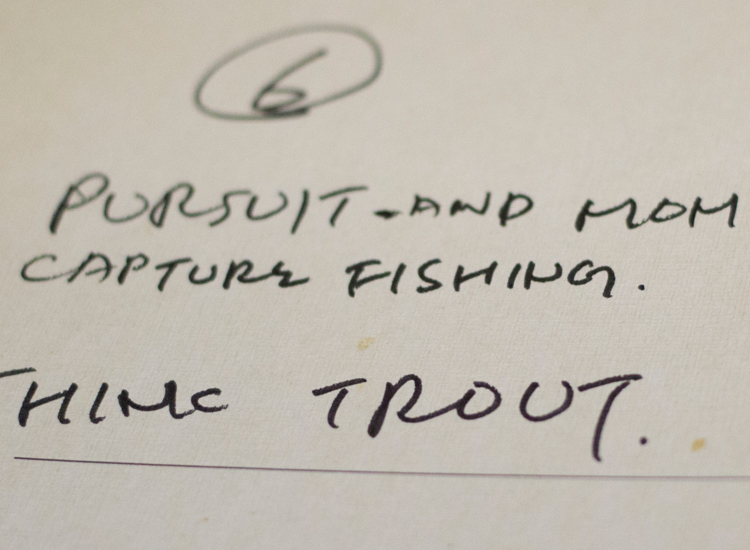

In 1974, Ashizawa traveled to the Rocky Mountains for the very first time for TV shooting of a nature program. What he was supposed to do there was to take a bike tour from Denver to Grand Teton National Park and to fish cutthroat trout (*3) in a spring creek (*2). It was the first experience for Ashizawa to do trout fishing in the U.S. At that time, there were only few Japanese tourists who visited the area and enjoyed fly-fishing in the middle of a vast wilderness. After the program created great impact on fishing lovers in Japan, the number of Japanese tourists and local guides increased around the area while travel agencies began to organize various tours there.

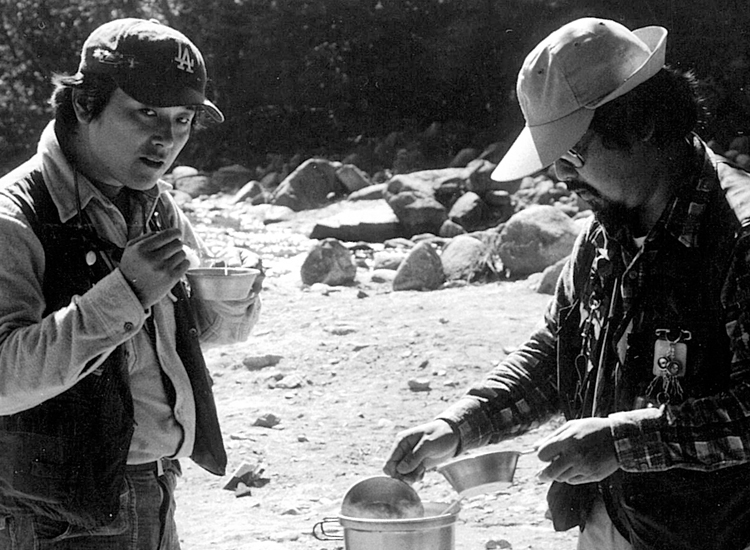

In the following year, Ashizawa organized “Outdoor Show” at a shopping building in Shibuya, showcasing authentic American outdoor sports gear and backpacking equipment with some materials. Since most of those products were not available in Japan then, outdoors men around the country gathered at the venue. And that was how Ashizawa met his sworn friend, Morio Sato. At that time, Sato was working at American Center Japan. Though he had enjoyed tramping from youth onward, he shifted his mountaineering style into backpacking after knowing it at his working place. “Masayuki Yui gave me an opportunity to meet Ashizawa. Yui was working at a store called “Sports Train” which handled imported products from the U.S. I knew Ashizawa before we met because he was on magazines. Ashizawa was one of the store’s customers and Yui told him about me.” Sato wrote about the encounter in the afterword of Ashizawa’s book “Kokyo no Kawa wo Sagasu Tabi (A Journey to Find My Hometown’s River).” “On the day, I took a freight lift at a carry-in entrance of the building with an old backpack on my back. When the lift stopped between floors and the doors opened, I saw Ashizawa standing in front of me. He was surprised and so was I. ‘Ah, you must be Sato,’ said Ashizawa. In fact, no one except me would carry a backpack in such a trendy shopping building, but he was too shocked to realize that. ‘Ah, yeah, I am. Er, are you Ashizawa?’ I stutteringly said so just like him. The man wearing a washed shirt, khaki six pocket shorts from sportif and Hardy’s fishing belt extended his right hand to me like Americans do. Also wearing a six pocket shorts from Levi’s, I grasped his hand tightly. (Six pocket shorts were considered as a symbol of backpackers then.)” Since then, the two had enjoyed various outdoor activities - fly-fishing, cross-country skiing, back-country skiing and camping - together. They also traveled around the world together for fishing or to find good products.

Attracting People in All Fields

To coincide with “Outdoor Show,” Ashizawa’s house became a regular party venue for an endless variety of people including fishermen, climbers, photographers, cross-country skiers, campers and editors. Of course, Sato was one of them. “What did we do? We all went there to chat. As dawn broke, we eventually got ready to go home. It was always like that.” And the social gathering was held every night. It must be so hard for Sachiko, the wife of the host. “Me? I was like a lunch lady (laughs). Ashizawa loved to get into various worlds. If he couldn’t talk enough with a person at a place they met, he would invite him to our house. And nobody rejected his offer. The guests ranged in age from teens to thirties and some of them were newlyweds. I think it was around the time when Morio (Sato) got his baby. Anyway all the people there were busy exchanging their knowledge and information without drinking. I guess Ashizawa was so happy to get friends who he could talk about what he loved. Everyone came to our place first thing after work and chatted. Then they had dinner and chatted again. I became a skilled cook because of the parties (laughs). If our guests missed the last train, they slept in a tent in our backyard and went straight to work (laughs).” Sachiko also told me a memorable story about Sato. “One day, Morio came to our place with his wife. As she said she had to leave earlier, I went to the nearest train station with her. Then she told me that she came with him to see what he was doing. She said he used to be a sober man and did only fishing besides working. But then he suddenly stopped to go home. She said her mother had advised her to see what he did because she thought he might have an affair. After visiting our house, however, she said she did understand what was happening (laughs). Since then we became close family friends. It was so fun and full of life.”

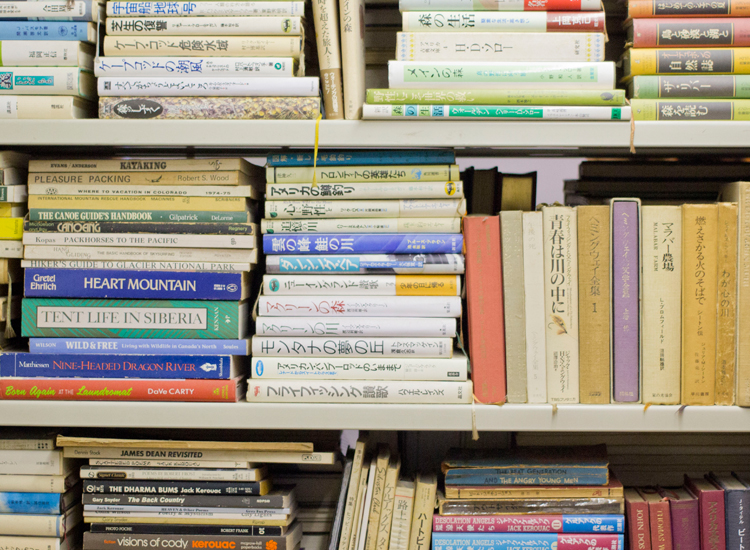

When Outdoor magazine was launched in 1976, Ashizawa joined the team as a graphic designer. In the same year, he published his first book “Backpacking Nyumon (The Introductory Book of Backpacking).” Although it is now so hard to find a copy of the book, Ashizawa introduced the backpacking boom in America to Japan for the first time through it. The most crucial section is definitely “Part 1: SPIRIT & MIND” in which he discloses the essence of backpacking not as a sport, but as a lifestyle to seek for coexistence with nature, explaining the activity’s historical roots and the predecessors’ thoughts. In the following sections, he gave detailed and passionate explanations of various outdoor equipment such as footwear, backpacks, survival gear and fly-fishing tools with a number of photos. For your information, Ashizawa took all the photos shown in the book in his backyard. Later he organized an event named “Great Outdoor Event” at Keio Plaza Hotel. Unlike today, people at that time normally got dressed up to go to a city hotel. During the event, however, there must have been so many people in outdoor clothes in the hotel. It looked odd but impactful, I guess.

Transition from an Outdoor Evangelist to Fly-fisher

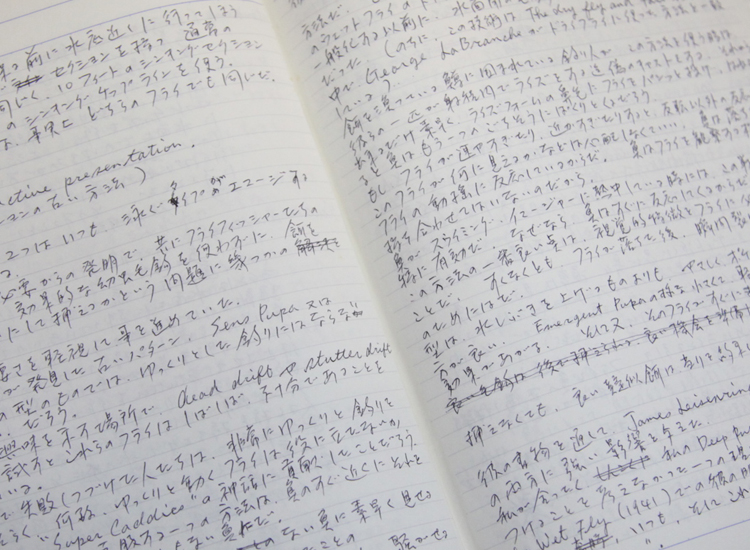

After translated Colin Fletcher’s “The New Complete Walker” in 1976, Ashizawa published his new book “Ashizawa Kazuhiro Shizen to Tsukiau 50 Syo (The 50 Chapters to Associate with Nature)” in 1978. He then became more into fly-fishing even people began to consider him as an outdoor evangelist. “When I think it back now, Ashizawa must have loved to fish and walk in Kazikazawa where he had visited with his parents. That was the reason he didn’t do sea fishing. He didn’t like a masculine type of fishing. Though he sometimes brought a few friends for fishing, he didn’t go in crowds. He would rather stroll to a river when he had some time. As well as Morio, people love fly-fishing had similar personalities. They were all quiet and preferred being alone. Ashizawa might have met those people in many different place and found a kindred spirit in them,” said Sachiko. Ashizawa also mentioned about fishing in his hometown, Kazikazawa. “It is a mountain town, and is also an old river port town with some traces of the glorious past. People like Hokusai, Hiroshige and Edward Weston got on board in this town. Kazikazawa smelled like a river. As I try to imagine the town, the feeling of the wind through river and the smell of a river quickly embrace me. (…) I see my sweet memories, my bitter memories and reddening clouds above a river. (…) Let me reminisce on old times. Now, I’m 10 year-old boy and It’s summer. (...) My father tells me to lift my rod skywards to lay the fish head-up. But I don’t do it. I prefer pulling the line slowly so that I can see the play of light created by shimmering water and fish. I remember that I loved it. (…) As my father tells me to go home, we empty out fish basket in shore. I remove the internal organs from fish and play with it. Then we count the fish we caught, spool our fishing traps and put our rods together to set off to home, glancing at insects gathering around a bare bulb. (…) I can recall the summer day so vividly after nearly forty years.” (From “Kyou mo Masu-zuri [Trout Fishing Again Today]”)

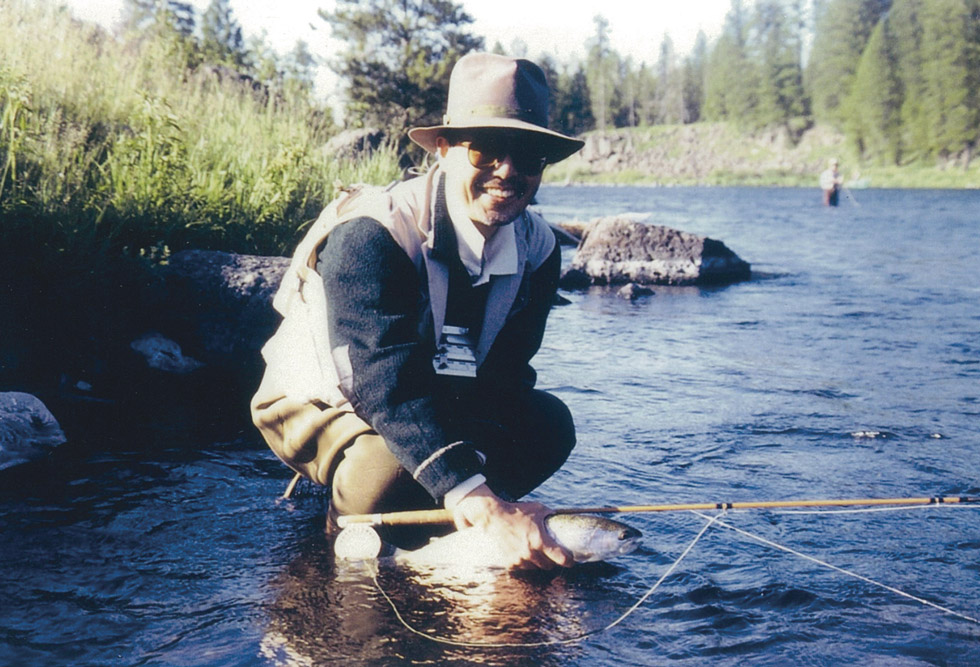

In 1978, Ashizawa hit the trail to an area near Yellowstone National Park with Sato. Because the trip doubled as a magazine coverage, Sato went to Los Angeles in advance for prior research and arrangements. After joining Ashizawa, the two traveled to Yosemite by land. Then they conducted a coverage tour from San Francisco to Anchorage afterward. The most memorable experience they had during the slog was fly-fishing in Yellowstone National Park (*4). Sato told me the story. “There is a river called Madison in Wyoming. The current is not so flat, but really productive. And fish in the river were so smart that they swam downstream quickly after we caught one. Although I could see them jumping in front of me, I had to think about various things beforehand such as where and how to land the fish. Once I caught fish, however, I got so excited and became eager to get more. But there was no fish around me. Even I chased downstream, they swam away again. Ashizawa tried to get some of them with me, saying ‘I would get them in my net.’ After some failed attempts, I finally managed to direct the fish into a slower part of the river, and Ashizawa netted it. I was deeply impressed when he said; ‘Sharing my joy with a trusty friend. That’s what fly-fishing is for.’ After shaking hands firmly with our guides who heartily congratulated our results, we released the fish into the same river. Everyone had love of nature and was conscious about environmental conservation in the U.S. In Japan, people often rejected the idea of ‘catch-and-release’ because of our custom of eating fish. Although rich nature is still left in Japan, it can disappear if we over-exploited natural resources. Ashizawa and I said that we had to do something for the future.”

s a way to live with nature, Ashizawa had advocated the idea of “low-impact.” He wrote about it in one of his publications. “Human beings are mere visitors! Yes, I think that is the most crucial point. I agree with the idea that wilderness and nature are the areas for human beings not to stay, but to just pay a visit. If we wish to come into contact with nature, we have to conserve it.” (From “Urban Outdoor Life”) “If I describe what I sought for in a few words, it can be ’low-impact’. I tried to find a lifestyle with as low impact as possible. That was it. Even when I enjoy outdoor living, the basis of our lives, I try to make it less impactful. Too much effort is, however, not necessary. I mean that you don’t have to be bound by accomplishment or do something beyond your ability. All you have to do is to listen to your inner self. (…) You also need to know that things you have chosen have to be somehow helpful. Your criterion of choosing must be backed by good reason. And the reason should be simple if possible.”

Establishing JFF to think about nature in Japan

Ashizawa established JFF (Japan Fly-fishers) with Morio Sato and the late Kenichi Murota. It was the time when Japan was in the middle of the bubble period and the rampant consumerism encouraged people to spend more and more money. And nature was affected by the economic condition. “There was no fish in a river. That was what happened in Japan at that time. People brought all the fish they caught. I don’t know whether they ate it,” said Sato. “In the postwar years of recovery, Japanese people planted a lot of cedar as building material. But cedar doesn’t help soil to catch rainwater. It just let the water go. And the leaves of conifers such as cedar provide food of low quality for aquatic insects. We should have more broad-leaf trees instead. Cutting broad-leaf trees grown naturally in a mountain will eventually affect the aquatic environment of tidal flats. Ashizawa and I wanted to think about it through fishing, saying a fisherman should always have things related to nature in mind and take action. We heard that American fishermen launched a campaign against a development of resort properties in the upper course of a river. Although the project was conducted by a major firm, it was cancelled in the end. In the country, fishermen already had an increasing say at that time. Because we wanted to spread the idea and background throughout Japanese society, Ashizawa and I decided to establish JFF.” The spirit of “low-impact” was passed down to JFF. “During the hippie era, young people in the U.S. were deeply influenced by Asian precepts of not to kill and not to fight. There was even a movement to incorporate the idea of Zen into daily life. Ashizawa tried to re-import the attitude to inspire Japanese people. He said we have to respect each other even in our lives in a city. He actually put the idea in practice.”

Ashizawa continued his fishing travel, visiting rivers in China’s Dalian and Andros Island within the Bahamas. Some of his masterpieces - “Fly Fishing Zensyo (The Book of Fly Fishing),” “Outdoor Monologue,”“Urban Outdoor Life,”“Genya wo Tanoshimu (Enjoying Wilderness),”“Yamamezato no Tsuri (Fishing at Yamame Village)” and “Back Country wo Meguru Totteoki no 14 no Hanashi (The 14 Best Stories on the Back-country)” – have been released around that time. Ashizawa got even better with experience both as a fisherman and as an author.

Moving on to New Chapter – Ashizawa’s Transformation to a Salmon Fisher

After getting a choledochal operation in 1993, Ashizawa made a comeback in his favorite fishing spot, Yellowstone National Park. In fact, he decided to be a salmon fisher in the place where he had visited for twenty years. We can read what he thought in that moment. “I kind of felt it last summer. By horse, I went to the third meadow of Slough Creek located in the back-country of the northern part of Yellowstone National Park to fish cutthroats. Putting my hands above a fire near my tent at dusk, I was watching moose gathering at the riverside. (…) And the idea suddenly came to me. I have had it! I would quit trout fishing. All of a sudden, I thought that. I’ve visited Yellowstone for twenty years. That seemed good time to leave off.” ‘(From “Kokyo no Kawa wo Sagasu Tabi”) Ashizawa traveled to Nova Scotia, a province located on the east coast of Canada. There he got a great opportunity to learn salmon fishing for the very first time in his life. Spending a few days to travel by car and airplane, Ashizawa finally met the Margaree River which he called “the river of fate.” “Ah how can I describe this feeling? I exchanged words with the river. No, that’s not right. The river actually spoke to me. It called me. To put its words into human language, I think the river said; ‘Here!’ I think it used women’s words. I felt that my body trembled with deep emotion. It was a mysterious, chilling feeling I have never had before. That is a feeling a man will have when he finds his own river. I think I felt something similar when I first saw Henrys Fork in Idaho. As I think over, however, the encounter wasn’t as inspirational as the one with the amazing Margaree River.”

The Endless Journey of the Legendary Backpacker

With a new vision of life, the salmon fisher made a trip to Iceland in 1995. “In short, I was enchanted by salmon. I was totally absorbed in the jump of the fish. That’s all. And I would like to say it again. There is nothing more beautiful than the salmon jump.” (From “Kokyo no Kawa wo Sagasu Tabi”) After writing so, Ashizawa fished Atlantic salmon in Laxa i Kjos river. Then he traveled to Tono of Iwate Prefecture to shoot a fishing program in the Sarugaishi River. And that turned out to be the last fieldwork for him.

“Standing on the river bank wrapped up with green lights, I cast a fishing line. Trout tried to get the bait and made ripples in water while salmon jumped up in the air. If possible, I would spend the rest of my life composing poems on rivers and salmon, intoxicated by happiness of being surrounded by nature.” (From “Watashi wo Yobu Kawa no Nioi [The Scent of the River Calling Me]”) Even on his sickbed, he always imagined the beautiful, productive rivers around the world. The legendary backpacker who had journeyed through life passed away on September 29th 1996 as a result of pancreatic cancer. He was 58.The cremains of Ashizawa are scattered in Henrys Fork in Yellowstone National Park by his family and friends. It was a bright, clear day and the water glistened in the sunlight. And JFF launched “The Kazuhiro Ashizawa Scholarship Fund” to carry out Ashizawa’s wish to cultivate green-minded young people through outdoor sports. The fund aims to support Japanese students and adults studying environmentology, animal ecology or other academic disciplines related to nature at universities in Montana. The establishment was greatly attributed to the effort from Steve Brown, a teacher of zoology at Montana State University, Bozeman and was Ashizawa’s best friend, along with full blessing from his wife, Sachiko.

Ashizawa’s second daughter, Maki, joined JFF because she enjoys fly-fishing, too. “People once visited my house and talked with my father now help me a lot. They are his legacy. Though I’m not good at fly-fishing, I just don’t want to lose the pleasant relationships.” She reads her father’s books over and over again. “I like the way he wrote. My favorite is ‘Back-country wo Meguru Totteoki no 14 no Hanash’ and ‘Genya wo Tanoshimu’. Actually I read it today, too (laughs). It’s embarrassing, but I learned about paintings by Winslow Homer and music of Toru Takemitsu from my father’s books. Then I researched more by myself. I also love the story of white cotton shirt.”

Sachiko said her favorite is “Irving wo Yonda Hi (The Day I Read Irving’s Novel).” “I think he wanted to be a literary man. At the beginning, he said that he wanted to write a novel. The way he wrote is literary, or perhaps I should say, romantic. The book was the last work of him and he wrote about the half of the book in his hospital room. I typed his handwritten draft.” In 2014, eighteen years after Ashizawa went to his rest, ELK, an outdoor gear store in Yamanashi Prefecture, organized an exhibition titled “The Exhibition of Kazuhiro Ashizawa.” The owner of the store, Hitoshi Yanagisawa, decided to hold the retrospective show to commemorate the deed of Ashizawa. Tools and gear he used, a series of books and magazines he published/designed along with family/friend memorabilia were shown at the exhibition while screening of his documentary movie and reading sessions were also held at the venue. Yanagisawa organized all the events just because he wanted people in their 20s and 30s know Ashizawa’s achievements. In fact, Yanagisawa has also been influenced by the legendary figure. “I love fishing, too. And that was the reason I went to the U.S. I enjoyed traveling around and fishing there for one and half year, spending all my money. After going back to Japan, I opened my store. It was about thirty years ago. Since I wanted to be a rod builder, I asked Ashizawa for some advice. He said I should visit his friends’ places and, to my surprise, wrote letters to all the rod builders he knew. He was so kind.” When Yanagisawa recall the image of Ashizawa, what comes first is always the idea of “low-impact.”“Ashizawa told me about the idea from the very beginning. He said; ‘Our existence is already nature destruction. And the same can be said for fishing, camping and trekking. So you should always remember to care and give back to nature.’ He was such a warm-hearted man. His attitude was always so soft and he answered all my questions.” When I asked Sato about what he would do with Ashizawa if he were still alive, I saw he had tears in his eyes. I cannot forget his voice answering; “I would buy a plot of land and use there to talk about nature. I would also build a log cottage for our friends to gather.”

Kazuhiro Ashizawa didn’t proclaim imperative of nature conservation. Instead, he gently told us about the excellence of loving nature through many books. I wonder how he feels if he sees the current touristy landscapes of Japan or people living in such an environment. I want to hear his story, but it is impossible. All we can do now is to read his book to understand his ideas. I therefore reach out for his book on my desk and start to read it again. So that I can hear he talks.